October 2023: Music Theory, Barely Intermediate Edition

This month was still looking busy, so I opted for a project I could well work towards on commutes. Despite the amount of music that I actively engage with, I have had very little formal education in music theory. I can construct basic chords and more or less know my keys, even though I will need a few moments to calculate the signatures. I know in theory what a tritone is, and constructed sixth and seventh chords is really not that difficult to begin with. Chord progressions, for example, completely elude me though. This is going to be a mostly intellectual pursuit, since I'm prepping for next month - yes, we're doing *that* again - and am struggling with not quite trivial problems, such as doors and being bad at planning. And intellectual problems mean, that I once again, get to do a lot of reading.

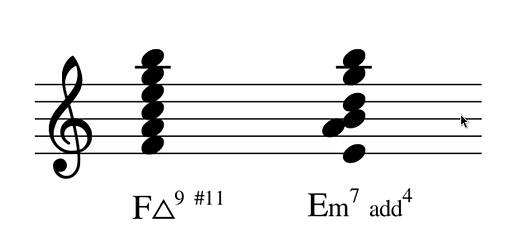

First of all, I want to take a look at chord extensions again. The basic set is pretty straight forward anyways. These are those major sevenths, for example, which place a large seventh on the root of the chord. However, as somebody who plays guitar mostly by chords, I'll sometimes encounter something that looks like this

and sure, I can just look up how to play that, and usually get a cramp in the metacarpal of my left thumb, but that doesn't necessarily tell me what I'm playing in theory. For that, it turns out that some kinds of chords have several notations, which is annoying, but also means that I don't need to panic, if a Delta pops up out of the blue. I'll source this section from beyondmusictheory.org.

Altered Chords

The most common extensions are major and minor sevenths, possibly because their construction is so naively intuitive. There's a bunch of descriptions in music that start with the letter "M", so sometimes the major seventh is noted as XΔ. One can consider these notations as a kind of constitution cipher. Where the actual name of a chord could be "Major 7th add #11", it can be written in short as XΔadd#11. The easiest extensions, apart from the sevenths, are ones that also feature a straight number. Something like the ninth, or eleventh. These just stack thirds until the largest of the intervals is the one noted down. If one just wants to add the ninth to - say - C minor, one would write Cm add9. The added notes can be preceeded by # or ♭ to either raise or flatten it. These are "altered chords", often found in jazz accompaniment. In a special case, the note is not part of the scale, but of it's parallel. In this case, it's a "borrowed chord". They don't have a separate notation, but have to be identified when encountered. A suspended chord retains the fifths, and replaces the third with either a second or a fourth, depending on whether it's a suspended second or fourth. Notation-wise this is all there is to it. Now we just need to learn how to use these to make things sound not garbage.

Modes

For theory noobs like me, there's really only two (and two-thirds) relevant musical scales: The major and minor one. They consist mostly of large second steps, with half-tones between the third and fourth (second and third for minor) and seventh and octave (it's complicated, but sixth and seventh in minor). The following is sourced from https://blog.landr.com/music-modes. Those exist as the base key that a piece of music is written in, but there's other scales that are used to introduce more flavour. These are what's considered the modal scales, of which there are seven. They are in order: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. As a musician, any system with seven or eight (or twelve) elements should immediately ring some bells, because of the cyclic nature of the regular scale. Indeed, these modal scales are constructed through keeping the notes of whatever key signatures we're in and starting with the n-th tone of the scale. Basically, they're the same scale as the base, but with an offset. For the sake of clarity: The Ionian mode has an offset of zero.

Every mode can be considered a regular minor or major scale with some alterations. Whether these alterations raise or lower the tone will give a lighter or darker impression on the mode. The phrygian, for example, is considered the darkest one, as a minor scale with three additional lowered tones.

Modulation

Modulation is the means by which one transitions from one key to another. There are several ways of doing this, each with its own effect and use case. The easiest (but potentially clunkiest) form is direct modulation, in which a chord in the old key is directly followed by one in the new one. This is the one I do, when I have to modulate, to varying effect. Hopefully, that repertoire can be expanded by doing this. It can be smoothed out a little by repeating an entire phrase in the target key. This is known as a sequential modulation. Common tone modulation is probably the most intuitive by concept. Most keys contain chords with common notes. It introduces an intermediary chord which consists of tones that occur in both the old and new keys, and then shifts the remaining tones by the half-steps into valid positions. Enharmonic modulation is easy to play, not so easy to identify. It's done by identifying a chord in the old key consisting entirely of tones that are represented in the new key, maybe changing their names but not their position. It's subtle, but often the chords involved look a little intimidating. Modulation by Pivot Chord requires finding one or several chords actually represented in both keys. When no such chords exist, one can choose altered common tone modulation. As an intermediate chord, one should pick one with the root in the target key center and has a chromatic alteration in the target key. Similarly when the modulation is done by half-steps only, it's considered a chromatic modulation. Where the modes come in is the parallel modulation, which changes the mode without changing the root. A more melodic approach is chain modulation, where the chords travel along an phrase, until the target key is reached.

Chord Progressions

One last thing, before I'm out of bullet points I was aware of looking up. Chord progressions are one of these things that (as far as I can tell) aren't really necessary for understanding music, but are definitely good to know, if you, let's say, dabble in playing the guitar or the piano. There's not really any set rules for these, and so the notation is fairly simplified. Instead of exact chords, we're usually given the root of the chord, relative to the tonic. The tonic is noted as "I", and we count up to VII. As in the usual diatonics, there's a distinction between primary chords and secondary chords of a key. These are I, IV, V and II, III, VI respectively. Chord progressions are meant to loop, so it should start and end on I, and the simplest chord progressions lean heavily on the primary chords. One such progression might be I IV V I. The secondary chords can be interspersed to add some spice.

A few closing words, before I wrap this up: There's technically a way of learning most of this that's not fractured into many different parts, and apparently that's the circle of fifths. It'll help with all the transposition stuff and with that give implications toward how to neatly get from one key to another. Probably, learning how that is structured and how to use it might be faster than these separate concepts, but as I saw it, I'd rather learn several very easy systems, in which I don't need to memorize much actual data. The circle of fifths has three columns, which I'd have to track, or just flat out memorize, which just isn't a thing I'm very good at, whereas starting with C and counting up the steps doesn't require me to memorize anything and one gets pretty fast at it with a little practice. The same with the discussion around modes, which is almost trivial, once the basic definition is down. For those who might be better served by models than lists, might want to check out the circle of fifths, but on the other hand, finding the aggregation of the different parts that make it up is a process that is a little more involved, hence, why the above might still be useful regardless.